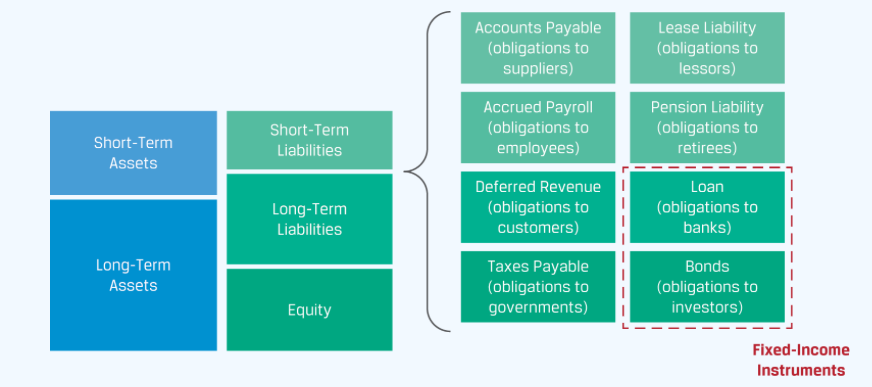

Fixed-income instruments are debt instruments, such as loans and bonds.

Loans are debt instruments formed and governed by a private agreement usually between an individual or company and a financial intermediary, such as bank.

Bonds or fixed-income securities are more standardised contractual agreements between larger issuers and investors.

A bond issuer borrows money most often to fund operations or capital expenditures. Bond investors are lenders who provide funds to the issuer in exchange for interest payments and future repayment of principal. While corporate issuers tend to have, at most, one or two types of equity securities outstanding, they often have many types of debt obligations outstanding, each with distinct features, such as time to maturity, seniority, and currency.

Issuer

A bond issuer can be any legal entity and is liable for all interest and principal payments.

Government sector issuers include national (also termed sovereign) or local governments, supranational organisations (such as the World Bank), and quasi-government entities (agencies owned or sponsored by governments, such as postal services or national railways).

Private sector issuers include corporate issuers and special purpose entities created to take ownership in such assets as loans or receivables, financed by asset-backed securities (ABS) issued to investors, which will be discussed in detail in later lessons.

Maturity

A bond’s maturity is the date of the final payment the issuer makes to investors, and the tenor refers to the remaining time to maturity.

Fixed-income securitieswith a tenor one year or less at issuance are known as money market securities.

Bonds with tenors longer than one year at issuance are called capital market securities.

Perpetual bonds are a less common bond type with no stated maturity.

Public sector entities were the first issuers of perpetual bonds, and current examples include local governments and local authorities, as well as certain bonds issued by banks to meet regulatory capital requirements. Perpetual bonds are still distinct from equities, however, in that they have contractually defined cash flows, no voting rights, and greater seniority in the capital structure.

Principal (Par or Face Value)

The principal, par value, or face value is the amount an issuer agrees to repay to investors at maturity.

Coupon Rate and Frequency

A bond’s interest can be paid as

- a fixed coupon paid on specified dates,

- a variable coupon determined and paid on specified dates, or

- part of a single payment with the principal at maturity.

Bonds with variable interest payments are called floating-rate notes (FRNs).

An FRN coupon is determined as a combination of market reference rate (MRR) and an issuer-specific spread referred to as the credit spread.

The MRR is a standard borrowing or lending rate for issuers with the highest creditworthiness or lowest default risk for different currencies and maturities. MRRs were historically determined by a poll of lenders (Libor) but transitioned to an average of observed market transaction rates.

Bonds that do not pay periodic interest and instead pay interest as part of a single payment with principal at maturity are termed zero-coupon bonds or pure discount bonds.

Zero-coupon bonds are typically issued at a discount to par; the difference between the issuance price and par value represents a cumulative interest payment at maturity.

Seniority

A debt issue’s seniority or priority of repayment among all issuer obligations is an important determinant of risk.

Senior debt has priority over other debt claims in the case of bankruptcy or liquidation.

Junior debt, or subordinated debt, claims have a lower priority than senior debt and are paid only once senior claims are satisfied.

Contingency Provisions

A contingency provision is a clause in a legal agreement that allows for an action if an event or circumstance occurs.

The most common contingency provision for bonds involves embedded options — specifically, call, put, and conversion to equity options.

Yield Measures

Given a bond’s expected cash flows and its price, return or yield measures can be calculated.

One simple measure is the current yield (CY), equal to the bond’s annual coupon divided by the bond’s price and expressed as a percentage.

A more complex but far more common yield measure is the yield-to-maturity (YTM), which is the internal rate of return (IRR) calculated using the bond’s price and its expected cash flows to maturity.

Yield Curves

Most fixed-income issuers have many debt instruments outstanding. A useful way of evaluating the YTM on one issue is to graph all an issuer’s debt instruments with identical features by their YTM and times to maturity. This graphical depiction results in a yield curve.